On Makar Sankranti, when the winter sun begins its northern climb, Haridwar is a poem in devotion. The mist hangs low over the Ganges, the temple bells hum softly, and the air smells of jaggery, sesame, and faith. I had come here with a friend — a devout Hindu visiting from London — who wanted to meet her family priest and update the ancestral record books. Her purpose was simple yet profound: to add the names of her grandchildren, born to her Catholic daughter-in-law and agnostic son, into the fragile ledgers maintained by the pandas of Haridwar for centuries.

These priests are the quiet archivists of Hindu memory. They keep immaculate genealogies of families they have never met — yellowing pages inked with names that map the journey of bloodlines and belief. My friend, practical yet deeply spiritual, felt that it was her duty to ensure the next generation was inscribed in those sacred pages. It was early morning when we drove toward the ghats, wrapped in shawls, our breath visible in the cold air.

The fog was dense, the streets still stirring awake. The priest had asked us to arrive by nine; until then, we decided to find tea. At the bus stop nearby, a group of women stood huddled against the cold. Their saris were thin, their faces drawn but alert. Each carried a small plastic bag and a tin lunchbox — their provisions for the day. As we waited for tea, curiosity tugged at us, and we asked where they were going.

“To the factory,” one said softly. They packed medicines for a large pharmaceutical company, she explained. The bus was late because of the holiday, but the factory wasn’t. If they arrived even a minute after eight, they would lose the day’s wage. They were all contract workers — hired through a middleman, with no benefits or security. They got twenty-one days of work and a week off, deliberately designed so that they couldn’t claim regular employment. During their off week, they either went home to their villages or worked elsewhere.

They refused our offer of tea politely; the bus could come any minute. “We’ll manage,” one said, her hands tucked into her thin shawl. They cooked together, lived together, and sent half their earnings home. In that moment, they seemed like a living constellation — women orbiting one another’s strength to survive the slow burn of the working class.

Among them were a few older women — widows, by the look of their colorless saris and bare arms. They stood silently, eyes distant. Some, we learned, had been left with the labor contractors by their families, their earnings sent home as remittance. It was another kind of bondage — not chains, but the quiet commerce of survival.

One of them, Sudha, was barely in her thirties. Her husband had been killed in a dispute over land; her in-laws blamed her for his death, calling her cursed. They starved her, shunned her, and finally sent her back to her brothers, who wanted little to do with her. Through a contractor, she found work in Haridwar’s industrial belt. She had never been to school but had learned to sign her name. She told us that for the first time in years, she could eat three meals a day and sleep without fear. She had learned the Gayatri Mantra from an older woman in her lodging and recited it every morning. “Maybe things will change,” she said, almost smiling.

As their bus finally pulled in, they climbed aboard — a flurry of colour and resilience. We finished our tea in silence. Haridwar’s holiness now seemed larger, more complex than before. The river cleansed, yes — but it also reflected.

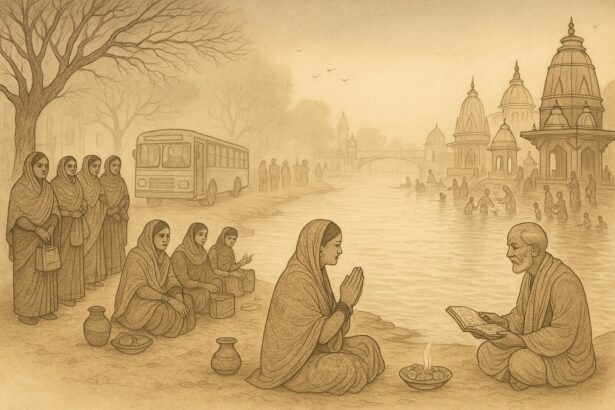

By the time we reached the ghat, the fog had lifted. The sunlight shimmered on the water like molten glass. My friend’s priest awaited her, a gentle man with a cotton shawl and a red ledger under his arm. She sat cross-legged by the river, reciting Sanskrit verses as he dictated them. It was once unthinkable for women to perform ancestral rites; only sons could do so. But now, here she was — daughter-in-law, grandmother, matriarch — performing the ritual for her lineage. Perhaps even the priests have realised the power of women, or perhaps, necessity has reformed faith in ways ideology could not. Either way, it felt right.

As she offered sweets and coins in a leaf bowl to the beggars, the wind picked up again. Children were selling incense, old men were chanting, and people were dipping into the river, trembling but determined. I watched quietly, aware that rituals have a way of holding both the sacred and the sorrowful — that life, like the Ganges, carries everything.

When it was done, we walked to a roadside dhaba. The samosas were crisp, the tea scalding and sweet. My friend seemed lighter, relieved, as if something unfinished in her family’s story had finally found closure. I thought of Sudha then — of all the women who wake before dawn, who pack medicines, who keep this country’s quiet machinery of endurance running.

The rituals of the priests and the rituals of labour — both are acts of faith. Both require repetition, belief, and unseen devotion. One preserves memory; the other sustains life.

That day, I realised Haridwar isn’t only where people come to cleanse their sins — it’s where the unseen women of India come to wash away silence. And as the river moved past us — ancient, indifferent, eternal — it seemed to whisper that all acts of persistence, however small, are forms of worship.

Sona Khan is an advocate of the Supreme Court of India. She is passionate about the subjects of Women and Development. She currently resides in the USA.